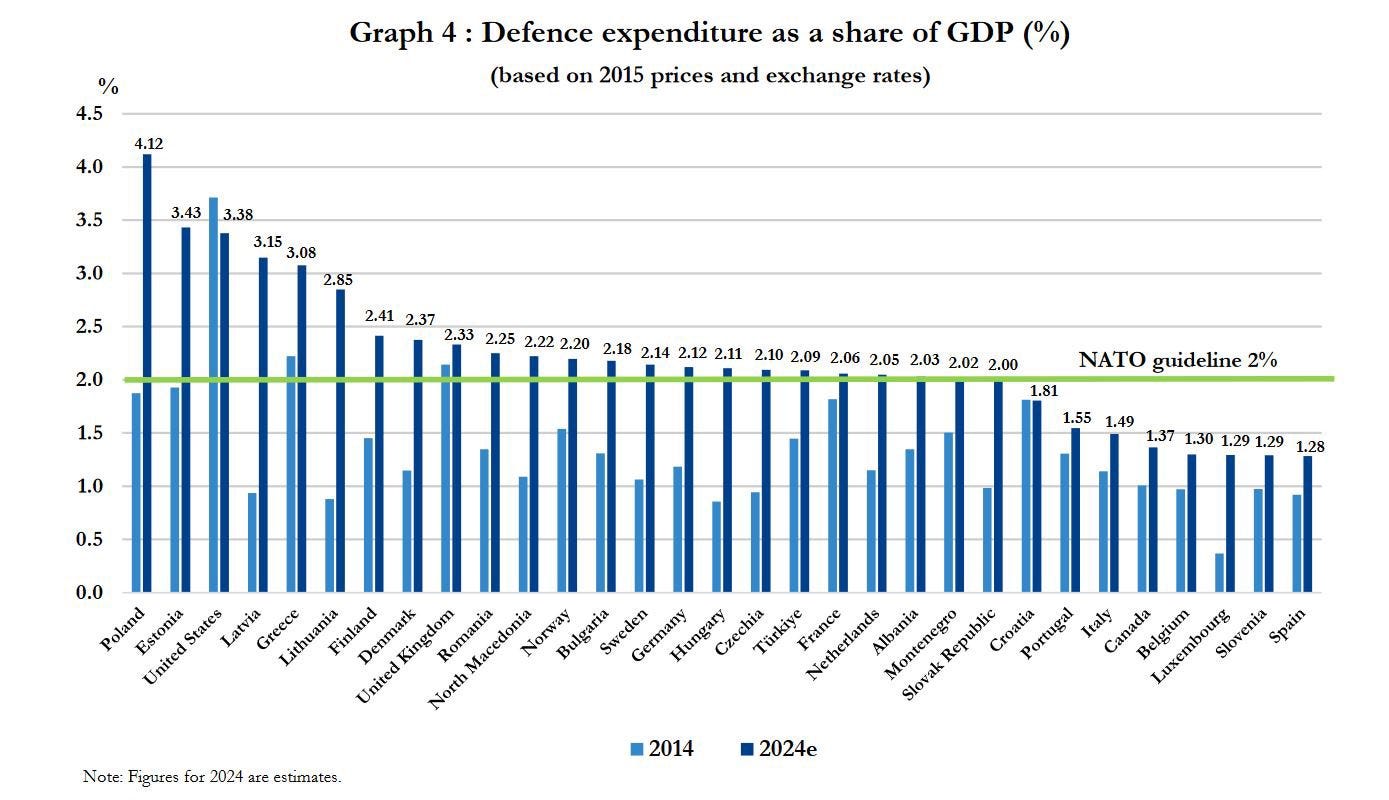

An increasing chorus of Americans contend that the NATO alliance has become effectively broken. They cite lackluster European defense spending, dwindling standing European NATO military forces, and a European military-industrial base that makes its anemic American counterpart look positively robust by comparison. In effect, European NATO still cannot defend their own continent against aggression without massive US assistance, even against a much weakened Russia. While the trend has begun to reverse in light of the Russo-Ukrainian War, the criticism remains a valid one. The question then becomes; how can the alliance reverse course and induce European NATO allies to behave responsibly on defense, thereby strengthening and preserving the alliance as a whole?

It’s a thorny issue. The NATO charter has no statutory means of compelling the alliance members. Regardless of their behavior, it cannot sanction or expel members once they are admitted to the alliance. This is despite the charter requiring certain behavior of the alliance members in the text of articles II and III as it relates to defense, economic, and foreign policy. Without an enforcement mechanism internally, or externally in the form of an omnipresent threat as existed during the Cold War, free riding has become endemic.

The resulting European military deficiencies have arguably been a contributing factor (one of many) to increased Russian aggression against unaligned states on its borders. This has prompted a large increase in American resources deployed for the protection of our European allies, and over $100B in direct aid to Ukraine to assist that nation against the Russian invasion. All while American strategists look at PRC aggression, and several other hot spots in the Middle East and Asia, with growing apprehension. In an increasingly hostile geopolitical landscape, the US needs its allies to be militarily robust and capable of mounting a credible local defense against regional hostile actors.

There is no material reason that (primarily Western) European NATO shouldn’t be able to accomplish this. On the whole, these nations have both the wealth and population to field credible military forces in line with their national limitations. In general, they choose not to and they have gotten away with that choice for decades.

In 1989, US forces accounted for 40% of all active duty NATO personnel. Today, among the 1989 allies, that number has risen to 47%. Even factoring in the new additions from former Warsaw Pact nations and neutrals, that number edges upward slightly to 41%.1

Unfortunately, despite some reported spending increases2, the corresponding increases in numbers have not materialized. Poland has indicated it wishes to increase the size of its forces to 300,000 personnel - by far the most aggressive planned increase of any NATO member, whether or not that target is attained remains to be seen. The UK by contrast is moving forward with plans to reduce its army to 72,500 troops by 2025, the smallest the British Army has been since the Napoleonic Wars.

As the Russo-Ukrainian War is proving once more, military mass matters. What a nation is capable of taking to war tomorrow in the event of a crisis is at least as important as overall defense spending. Currently, there may be some reform on the horizon for the latter, but precious little effort is being devoted to the former, with notable exceptions.

How then should the US go about inducing the European allies to both spend more and increase their force levels to a point where they can effectively defend themselves without massive US support being required at all times? Presidents Bush and Obama both attempted to exert conventional pressure in this arena with limited success. Even overt threats by President Trump, in a much more strident departure from his two predecessors, only produced modest changes. What moves the needle for European politicians is the perceived risk to their own nations. This is why the Russo-Ukrainian War is beginning to alter European behavior in ways the pleas, entreaties, requests, demands, and threats of three American Presidents failed to do.

With this as our guiding principle, the solution from a US perspective is practically simple, though it will require considerable political will to carry it out and persevere in the face of the inevitable wailing and gnashing of teeth it will generate. The US must stop doing for Europe what Europe could and should do for itself. This is not to say America shouldn’t liaise closely with and exercise regularly with our allies. But the active deployments, and potentially even some of the garrisons, the US has maintained explicitly in defense of Europe should be turned over to European forces.

This effort should start small and our allies should be warned well in advance of the change in US policy to allow them to prepare. The goal is not to punish our allies, just the opposite. The objective is to induce them to behave responsibly by presenting them with a choice: Attend to their own security needs or accept the risks that come with failing to do so.

A prime candidate for the initial offering in this effort would be the withdrawal of US forces in the Balkans. The US has had troops in the region as part of the NATO Kosovo Force (KFOR) mission since the late 1990’s. Currently, there are 572 American personnel assigned - a number existing European NATO members could easily make up if they wished to do so. Moreover, this deployment has been effected purely to salve European fears of another Balkan conflict. Exactly the type of concern European allies could and should be dealing with out of their own resources.

Critics of this proposal will (and have) demanded a continued US presence on the basis that US troops deter aggression in ways purely European forces do not. This underlines the necessity of the action. What they are saying, in effect, is that European militaries aren’t taken as seriously as the Americans. They’re right, and that won’t change until those European forces are forced to assume more responsibility with success or failure riding on their performance.

The current global security environment is tumultuous, and getting worse. There is a major land war in Europe, another war in the Middle East, North Korea is using the Sea of Japan like a driving range for ballistic missiles, and the PRC is behaving increasingly aggressively against several of its neighbors - notably the Phillippines and Taiwan. In these circumstances the US cannot, and should not have to, militarily babysit Europe as if it were still 1945 or even 1987. There is no reason Europe cannot address the lion's share of its own security concerns out of its own resources. If the only way to induce that behavior is to stop doing it for them and force them to assume the responsibility or run the attendant risks of not doing so, so be it.

Data drawn from IISS’s annual Military Balance Reports from 1988-1989 and 2023-2024.

https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2024/6/pdf/240617-def-exp-2024-en.pdf

Neither of the corrupt parties we have in the US care enough to seriously try, but what we should do is pull out of Western Europe as much as possible and move all we can to Poland, the Baltics and Ukraine after the war. Maybe Finland as well.

The UK wants to be so weak they couldn't even defend their own island, so we shouldn't be there any more than a logistical hub to get us to our eastern european bases.

Every base in Germany could be moved to Poland, Ukraine or the Baltics.

Leave every country that isn't taking their defense seriously, leaving only logistical bases if they're absolutely needed to get to our bases in eastern Europe.

US forces act also a tripwire - "mess with the best, die like the rest".