Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Ugly Reality of Warfare

Harry Truman's hard choice saved lives.

August 6th and 9th marked the 78th anniversary of American nuclear weapons use on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki respectively. While at the time this was regarded as a war winning necessity to save lives, today a great many world leaders have taken to decrying it as a black mark on the United States – an avoidable atrocity we must now be ashamed of. This is illiterate historical revisionism of the highest order. Instead of this facile pandering, it would be far better if we embraced this harsh lesson on the realities of warfare as a warning to future generations.

By mid-1945 the Second World War was coming to a close. The Third Reich had capitulated to the Allied forces in Europe on the 8th of May, while American and Commonwealth troops continued to grind their way across the Pacific Theater, eliminating Imperial Japanese strongholds one by one. As they made their way inexorably closer to the Japanese Home Islands, Allied planners began drawing up an operation for a conventional invasion of the Japan itself. Their estimates were staggering even by the brutal standards of the Pacific Campaign.

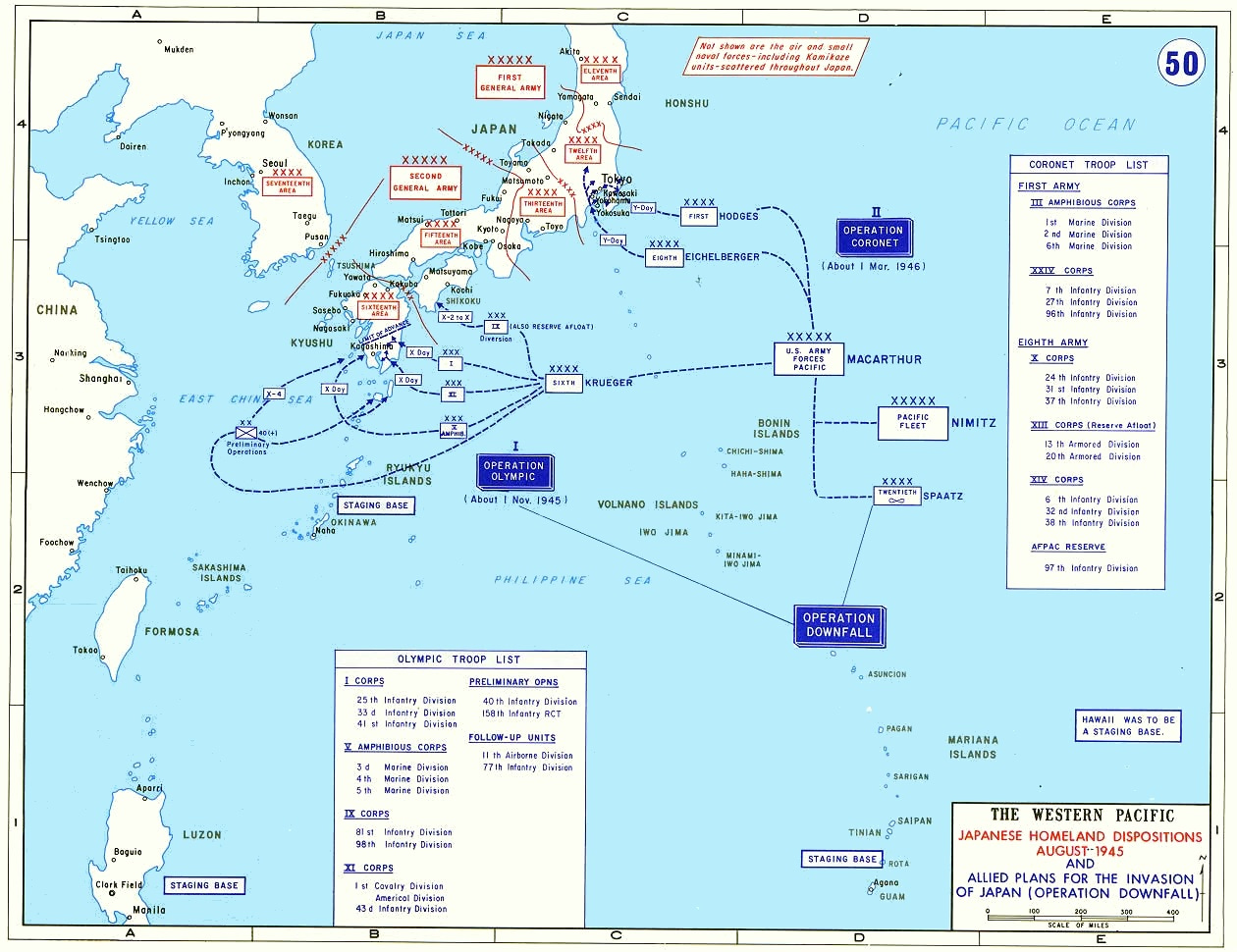

Using the overall codename Operation Downfall, the aim was to land 15 US divisions of the US 6th Army on the island of Kyushu. This first landing was to be called Operation Olympic, a second landing aimed at Tokyo called Operation Coronet was to take place on the island of Honshu some time in 1946 and consist of a further 15 US divisions, to be reinforced by a further 12 US divisions and 3 British divisions. Should the initial landings in 1945 run into trouble, the Coronet units would be used to reinforce them. US Army planners expected the overall conquest to run into 1947 at a minimum.

Casualties were expected to be hideous. US Army planners ballparked their projected losses by 1947 at 863,000. They estimated around 43,000 casualties a month. Other assessments were even more pessimistic, postulating the US would need to ship in 100,000 fresh soldiers every month in order to maintain offensive operations after the initial landings on Kyushu. Gen. Curtis “Bombs Away” LeMay estimated the entire plan would cost the allies half a million dead. Adm. Nimitz’s staff thought casualties would be 49,000 in the first 30 days. Gen. MacArthur’s staff estimated 125,000 after 30 days of fighting on Kyushu, though their assumptions of Japanese opposition only accounted for one third of the over 900,000 defenders on the island. Gen. MacArthur’s Chief of Staff, Maj. Gen. Willoughby, estimated between 210-280,000 casualties just to secure a third of Kyushu island. As of 2020 the Purple Hearts (US military decoration for personnel wounded in action) minted in anticipation of US casualties in Operation Downfall were still being issued to American servicemen for wounds sustained during the War on Terror.

These horrific expectations had a sound basis. As allied troops edged ever closer to Japan itself, Imperial Japanese troops fought increasingly stubbornly, and in fact suicidally, to resist them. During the Battle of Okinawa US forces suffered over 50,000 casualties in 82 days of fighting. At Saipan the previous year, over a thousand Japanese civilians had thrown themselves from a cliff to avoid being captured by the Americans. American planners were already gathering intelligence indicating the Japanese were training their civilians to rush the landing beaches with bamboo spears in human wave attacks that had become an all too familiar hallmark of Imperial Japan’s military personnel when all other hope was exhausted.

The Americans were faced with a sobering reality: their military might be forced to conduct what amounted to a campaign of genocide in order to end the war. In fact, that may have been the Japanese plan. If they could make the entire operation a sufficiently bloody one for all sides, the US might be willing to negotiate terms rather than press for an unconditional surrender. This was articulated bluntly by Adm. Takijiro Onishi, vice chief of Japanese naval operations, when he said “If we are prepared to sacrifice 20 million Japanese lives, victory will be ours!” Some alternative had to be sought, but what?

Harry S. Truman had been thrust in the role of leading America in the final days of the war after the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in April of 1945. Among the many things he was informed of on assuming the Presidency was the existence of something called the Manhattan Project - the American effort to develop nuclear weapons. It had been cloaked in such a degree of secrecy that not even the Vice President had known of its existence. But, if viable, it offered an alternative to two more years of sheer butchery in the Pacific. Perhaps, it was thought, Japan might surrender if it could be overawed by the possibility of its own annihilation without the Americans having to risk hundreds of thousands of their own casualties.

In the end, President Truman gave the order to use these new weapons. On August 6th Colonel Paul Tibbets of the 393rd Bombardment Group flew his B-29 bomber, the Enola Gay, from their field on Tinian Island and eventually deployed the first atomic weapon ever used in warfare. Named “Little Boy”, it detonated over the city of Hiroshima with a force of around 15 kilotons of TNT. The blast created widespread devastation, set off massive fires, and likely killed between 90-150,000 people - the majority of whom were civilians. After calls to surrender went unheeded, a second bomb was dropped.

The Nagasaki mission was flown by Major Charles Sweeney flying the B-29 Bockscar on August 9th, also originating at Tinian. Their payload, the bomb named “Fat Man” was deployed over Nagasaki and detonated with a force of around 21 kilotons of TNT. The blast was even more destructive than that produced by “Little Boy”, though channeled and confined by terrain. It likely killed between 60-80,000 people, again mostly civilians. The US planned to have three more “Fat Man” type bombs available per month in September and October. Fortunately, these proved unnecessary.

On August 12th Emperor Hirohito made the decision to formally surrender. After extensive consultation, he recorded a surrender broadcast that was to be played to the nation on August 15th. This was nearly halted when over 18,000 military personnel, led by officers from the Ministry of War and the Imperial Guard, attempted a coup to imprison the Emperor and extend the war on the night of 14-15 August in what became known as the Kyujo Incident. Casualties were very minor and after the putschists failed to convince the rest of the army to accept their plan, the leaders committed ritual suicide. The Emperor’s surrender broadcast was delivered on August 15th and effectively ended the war. It is the first known instance of a Japanese Emperor addressing the common people en masse.

The 230,000 deaths produced by the two bombings were (depending on sources) either about equal to or half of what allied planners estimated their own combat fatalities would be as a result of a conventional invasion and two years of fighting. They were just over 1% what officers like Adm. Onishi were prepared to sacrifice to continue the Empire. Allied firebombing raids had likely killed more than twice that number earlier in the war, including the Tokyo attack on the night of 9-10 March that resulted in a firestorm that claimed the lives of between 80-130,000 civilians. Yet it is the nuclear bombings that garner so much modern anguish.

Japanese leaders can certainly be forgiven for wishing for a world free of nuclear weapons. However the cacophony of derision coming from academics, diplomats, politicians and others outside Japan is far less tolerable. These were appalling events that claimed the lives of a quarter million people as the final act of a war that claimed tens of millions of lives. Their horror should serve as a reminder and a warning to all those who contemplate a return to the days when conventional warfare was a far more common occurrence. The atomic bombings also saved lives.

The evidence against this is indisputable. Despite what Communist sympathizers would have you believe, the Soviet Union’s entry into the war against Japan on August 7th, just in time to snap up some territory, had virtually no impact on the willingness of Japan to fight to the bitter end. Despite the contestations of peaceniks that the bombs were unnecessary, events prove that even after the use of nuclear weapons and in spite of the orders of their Emperor, the Japanese military had elements within it that would have preferred to die fighting. Millions of people; American, British, and Japanese, are alive today because Harry Truman had the courage to unleash the unmitigated terror of nuclear weapons.

In the intervening years those same nuclear weapons and the legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have kept the world free of large scale conventional conflict between major powers. No two nuclear equipped nations have engaged in wars of conquest against one another post-19451. Conspicuously, the threat of species extinction kept the Cold War from turning hot for almost 50 years in the latter half of the 20th century. This is no accident, the warning of Hiroshima and Nagasaki continues to provide ample evidence that such a conflict would leave no winners, only survivors.

The decision by the United States to use atomic bombs to end the Second World War was a right and just one. By any measure it saved lives compared to every other viable alternative. Moreover the threat of such weapons being used again has served to reduce the frequency of large conventional wars between powerful nations. We should not hang our heads in shame and apolgize when the anniversary of their use rolls around. Nor should we allow their use to be a platform for advocating nuclear disarmament - this is as ignorant as it is dangerous. Instead, the atomic bombings should be noted and discussed for the grim lessons they are. Lest another future American President be forced into the same kind of decision as Harry Truman in 1945.

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1999 could be seen as an exception to this point, though I would argue as it was fought entirely in Kargil Province of Kashmir which both sides have long disputed, itwas a border conflict and not a war of conquest against recognized sovereign territory.

What would have happened if the US had not dropped the bombs on Japan? No one knows, but nuclear bombs might have been used against people somewhere else, and it might have been in a way that would have had more disastrous consequences. Japanese learned a lot from the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as the damage they did. The fact that nuclear bombs have not been used in war since is a silver lining that humanity can learn something from such tragedies.

There is no doubt that there were Japanese in the heart of the military who were literally willing to fight to the death. From the Japanese perspective, the Kyujo Incident tells us that the atomic bombings did not force the mainland war faction to admit defeat, although the deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians undoubtedly changed the balance of power between the peace and mainland war factions among Japanese political leaders. The dropping of the atomic bombs played a decisive role in Japan's immediate acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration (i.e. unconditional surrender), but does it really mean "By any measure it saved lives compared to every other viable alternative"? For example, was it necessary to drop an atomic bomb on Nagasaki in addition to Hiroshima?

I am not here trying to argue that the bombing of Nagasaki was unnecessary. However, I don't think the stories and data you post really support "By any measure it saved lives compared to every other viable alternative".